Digital Ancient Near Eastern Studies - A Transition to Arts and Crafts

“The use of electronic data-processing devices for research in the fields of linguistics and philology is by now fairly common.” (Hans G. Güterbock, “The Hittite Computer Analysis Project”, from the 1967-1968 annual report of the Oriental Institute, currently the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures)

Digital studies of the ancient Near East are not new. If anything, within the fields of assyriology, egyptology, and archaeology, one can find some of the pioneers embracing the advent of the computer age. Today, there is new interest in applying computational methods to the humanities and social sciences, and to the study of the ancient world specifically, given the potential of such interdisciplinary initiatives. However, there are questions that are fair to ask:

can the computer really teach us something new about our fragmentary, complicated texts and artifacts? Is this a movement of new arts and crafts, providing us with fresh perspectives, or are these arts and crafts a trending hobby, not really worth the scholarly effort?

In order to apply computational methodologies, there is a need for shared language, interdisciplinary work, and a willingness to constantly learn outside of your field of specialty. Exploration of texts and artifacts as data, with the plethora of tools and techniques available today, is fundamental, yet figuring out where to start can be daunting. There is a need to design experiments, that might fail, and show no results except (bitter) experience. Even the significance of successful results are not always appreciated by your peers. Where computational analysis ends or should end and humanistic inference begins can at times be opaque. Lack of standards and resources for computational research in ancient Near Eastern (ANE) studies and neighboring disciplines makes the interpretation and significance of such work vague and unclear to the non-specialists.

Let us give such an example. Below you can see graphs generated from the network of the Mesopotamian Ancient Placenames Almanac (MAPA); for further information see Gordin, Clark and Romach (2022) and Clark and Gordin (2023). The points on the graph are toponyms attested in texts from the hinterland of the city of Uruk in the first millennium BCE. Their position on the graph is a result of their Degree in the network—how central they are as hubs—and their Betweenness Centrality score—how important they are as a bridge to get from one location to another.

Without minimal background in graph theory, it is hard to understand the value of such visualizations, and whether they add new information to our traditional ways of understanding connections and links between geographical locations. The transformation of the texts into data—from sentences to word lists, to toponyms represented in a network, to a graph of their scores—distances us from the artifacts, the original texts. These transformations are so substantial, it is the equivalent of looking at a sword and trying to understand how it was forged without seeing the process or knowing anything about the tools and methods used.

In this piece, we argue that it is worthwhile to dedicate the time to learn these arts and crafts. We begin with what resources were created before us, where we stand today, and what we hope to gain in the future. We outline the initiatives of the Digital Ancient Near Eastern Studies (DANES) network, whose purpose is to increase the number of apprentices, by providing both basic literacy to understand computational methods, and advanced practical applications to those who want to become artisans in the field.

Foundations

The early pioneers created large databases which are the baselines for many computational works performed today, such as (in alphabetical order) the Coptic Scriptorium, Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI), Hethitologie-Portal Mainz (HPM), the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus (ORACC), Papyri.info, the Perseus digital library, and Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae (TLA), to name a few. Most of these efforts were placed at digitizing ancient sources. This was a colossal effort with the technology of the time, when storage space was limited, when punch-cards were frustrating, when non-Latin characters were not supported.

The first wave of digitization now seems lost to recent history, with many mixed results that cannot be fully surveyed here (see Sahala 2021, ch. 2). Centers like the Centres de mécanographie documentaire pour l’archéologie (CDMA, later CADA) initiated in 1957 by Jean-Claude Gardin, were not only the first to make machine readable versions of Mesopotamian texts (Plutniak 2018), but also published computational historical studies using, for example, graph theory and network analysis (Gardin & Garelli 1961 on Old Assyrian commercial networks). Other foundational projects, that continue until this very day in different iterations, include the Neo-Assyrian letters of Simo Parpola in Helsinki during the 1960’s (now the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, and the related Munich MOCCI project), and Buccellati’s Cybernetica Mesopotamica (see its many publications, as well as a topical index).

Criticism was not lacking towards these revolutionary endeavors. Were digitization and computational studies worth the effort? Was new knowledge obtained that could not have been gathered otherwise? Such setbacks conceptually made it seem as though the computer revolution has not fundamentally touched upon the fields of the ancient Near East. There are still general misunderstandings regarding the inherent differences between print publications (which include PDF versions), and plain-text digital scholarly editions that are also published on online platforms (see Sahle 2016).

From the early 2010s, the AI revolution reinvigorated the use of computational methods for the study of the ancient Near East. Breakthroughs in computer science, increased storage capabilities for big data, the development of the internet, the creation of programming languages and environments that are more user-friendly, and the extension of the Unicode standard, opened new lines of research.

At the current moment, we think a conscious choice needs to be made on how we envision the field going forward. If we want to promote new methodologies, we cannot dismiss established ones. If we want to promote such new methodologies alongside established ones, computational research needs to be communicated in a way that is still understandable to all relevant fields. We need a shared language that includes basic literacy of terms, common problems and possible solutions (see e.g. Homburg et al. 2023). As basic digital literacy becomes more common, more scholars and students will desire to expand their knowledge, use digital tools, gain more programming experience, etc.

This is particularly important as computational methods are shared across the growing field of digital humanities. A shared set of methodologies is a powerful link between fields, creating a shared jargon, and it is important that we propel the study of ancient cultures to current research avenues.

Training in the Present

All the above requires training—both of humans and machine learning algorithms. The barriers to computational studies today for those coming from the humanities, compared to the challenges of the 20th century, are very different. Yet, the big difference is that today it is easier to lower said barriers, due to the ease of sharing information, tools, and knowledge online. There are many digital humanities’ initiatives, platforms, and resources, to train and aid humanists to learn anything from basic digital literacy to developing advanced machine learning applications (such as the Programming Historian, The Digital Orientalist, or DARIAH-Campus). These general resources are invaluable, but sometimes they are insufficient when applying new methodologies on ancient Near Eastern data, either in the form of text, object, image, or landscape.

Furthermore, current technologies, especially generative AI models, offer new possibilities. Large language models (LLMs) have transformed the ways in which we interact with texts only in the last few months. Many are wondering what is the place of humans in this future, now that generative models such as GPT and image generation models are revolutionizing the way we write and create. Barriers such as the knowledge of how to write code may seem obsolete, now that anyone can use chatGPT with natural language input to program. Nevertheless, that does not mean that anyone can write useful and functional code, or gain meaningful results.

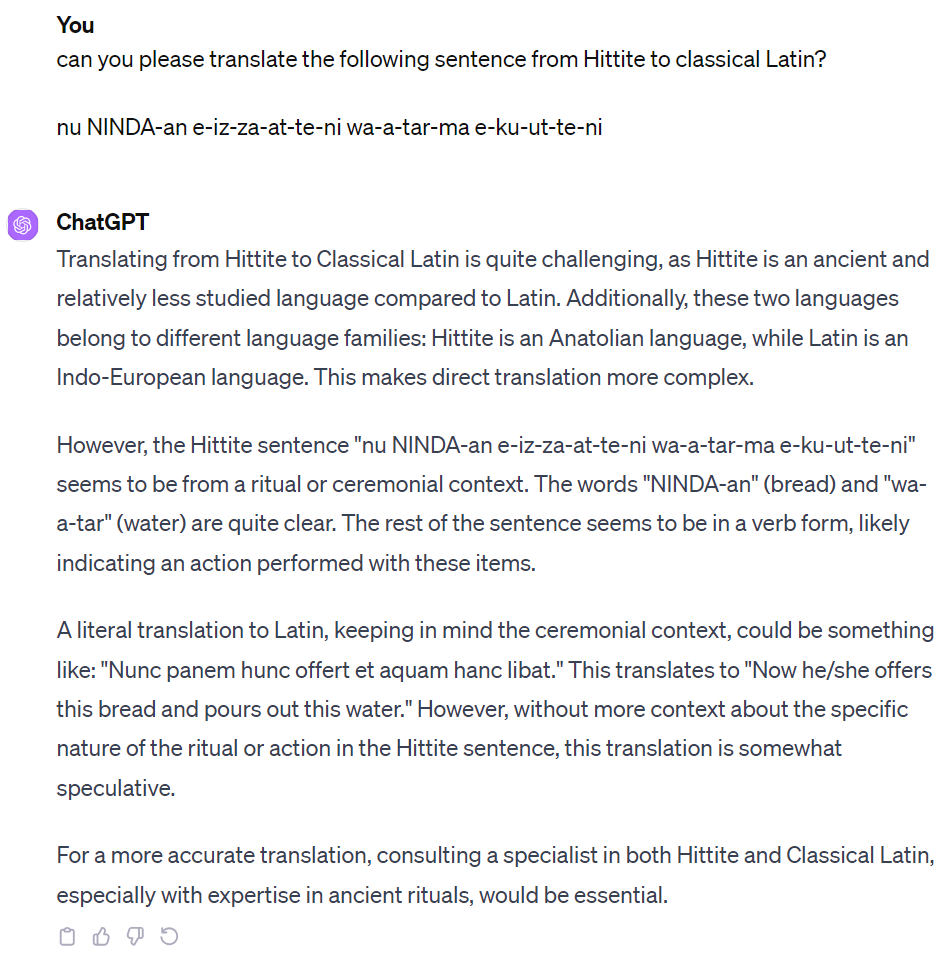

It is easy to trick or ask ChatGPT questions the model was not trained for, and receive incorrect results. When asked to translate a pivotal sentence in Hittite that was used for its identification as an Indo-European language, the translation is only partially correct, with many caveats elaborated upon by the model, such as the incorrect statement that Hittite and Latin are from two different language families!

For humanists to be able to understand how to work with such tools, and gain meaningful results from AI models, digital literacy is a prerequisite. In the above example, knowing more about what language models are to begin with, what data they are trained on and how it affects the model’s results, allows humanists to judge their results accordingly and also teaches humanists how to give only reasonable tasks to models to begin with.

On the other side of the coin, those with computational background are often not familiar enough with the intricacies of ancient cultures, languages, writing systems, and artifacts in order to design models that will provide historically sound results or meaningful conclusions. Conceptual understanding and structured ontologies are imperative for scholars from the humanities to better contribute to the methodological discussions in the interface between computational methods and humanistic approaches.

Furthermore, despite the foundational works of the 20th century, we are still facing issues that are waiting for state-of-the-art innovations when studying ancient cultures computationally. We should update our best-practice methods for preserving and digitizing our objects of study. While the vast majority of image data are photographs and flatbed scans, the number of acquired and available 2D+ and 3D models is increasing. 3D models specifically provide precise representations that allow the exact measurements of minute details such as fingerprints, seals and damaged characters. Standardized high-resolution, high-contrast representations have also been shown to improve AI-based approaches to optical character recognition tasks (Stötzner et al. 2023). To take advantage of these new technological possibilities, 3D scanning needs to be put on the agenda, and its benefits for research and object preservation need to be clearly communicated to the wider research community.

For fully transparent research and seamless workflow, these material remains need to be linked to metadata, or text editions if there is any writing on the objects. Linked open data (LOD) is a set of standards for linking data (be it text, artifact, metadata, and more) over the web in certain formats, following specific ontologies agreed upon by a community of experts. The use of LOD in ancient studies is growing (e.g. Pelagios network), and it requires consensus and discussions to keep the data interlinked.

Digital monolingualism and the primacy of the Latin script have led to software development lagging behind a fundamental need for full Unicode and font support in order to include non-European scripts and languages. Natural language processing (NLP) models designed primarily for English and maybe some other European languages require adaptations when applied to ancient languages. The need for a lobby of ancient Near Eastern studies and other disciplines sharing these concerns is obvious (see for example the DHd Multilingual Digital Humanities working group), and ancient language processing (ALP) is becoming a growing initiative within the NLP and machine learning community (see e.g. Anderson et al. 2023, Bin and Gordin 2023, and the ML4AL workshop @ ACL 2024).

In the next section, we elaborate on the work of the DANES community to furnish some of the prerequisites necessary for meaningful computational and collaborative research, and to promote research on some of the current issues presented above.

Current and Future Activities

The DANES network actively creates spaces for the above goals to become a reality. The efforts of the network, which is inclusive and welcoming to all interested scholars and students in relevant fields, are manifest through the following initiatives:

Conferences

The first annual DANES conference took place between 19th-21st of February 2023, organized by three institutions: the Digital Pasts Lab at Ariel University, the TAD AI and Data Science Center at Tel Aviv University, and the School of Computer Science and Engineering at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The conference covered many topics, including optical character recognition (OCR) for cuneiform documents, data visualization methods, critical discussion of data analysis and machine learning, computational stylistics, natural language processing models, linguistic annotation, networks, and new online tools and environments and their sustainability. One can view the talks of the first day on YouTube, read the abstracts on Zenodo, and view the conference posters on OpenDANES. The proceedings of the conference are going to be published as a special issue, iDANES, in the it - Information Technology journal.

Just as important as the talks themselves, were the discussions in-between sessions, the discovery of shared problems, and arriving at joint solutions. These conversations led to more avenues of further development and collaboration. Such was the main purpose of the conference: not only giving a venue to present interdisciplinary research, but also a space for scholars that usually have few people around them that understand every aspect of their work.

The conference included a Q&A session with some of the experts in the field, Eliese-Sophia Lincke, Niek Veldhuis, Hendrik Hameeuw, and Hubert Mara, who received questions from the audience and online participants on some of the current burning questions. Especially important were the round-table discussions, whose purpose was to establish the goals of the new DANES network, common points of contention, future areas of research, and what is needed for the network and this field to thrive in the next decade.

DANES conferences are going to regularly occur every year. The exact date of the next conference is still in the works. The following conferences will continue to have a combination of lectures with active participation: hands-on workshops, round-tables, and Q&A sessions.

Working groups

The DANES working groups are usually once-per-month online meetings to discuss or implement a specific computational methodology. In between meetings, the DANES discord server has sub-channels for each group for further discussions. They are meant as an entry point for those who want to learn about computational methodologies and do not know where to start or whom to ask. They are usually led by at least two people from the network.

In 2023, the OCR group, led by Hendrik Hameeuw and Eliese-Sophia Lincke, met to discuss current challenges. The ancient language processing (ALP) group, led by Katrien De Graef and Shai Gordin, had guest lectures of various experts in the field to discuss their ongoing projects; the lectures and the recordings are available. The Interoperability and annotation group, led by Adam Anderson and Timo Homburg, discussed the importance of linked open data and how to apply it.

Specific topics for groups depend on the initiators. Anyone is welcome to lead a group! Current active groups include a continuation of the ALP group, this year focusing on how to create a framework of under-resourced ANE languages, with a case-study on Elamite. Further activities of the Pedagogy and Gamification group and OCR groups are planned for 2024—sign up for the mailing list or join the Discord for updates!

Discord and mailing list

The channels of communication for members of the DANES network is through Discord and a mailing list. To join the mailing list or Discord, send an email to danes@listserv.dfn.de or digpasts@gmail.com. Discord is a communication platform that allows users to create and join communities, known as servers, where they can chat with text, voice, and video. It was originally designed for gamers to communicate while playing online games, but it has since expanded to cater to various interests and communities. The DANES discord server includes various channels for communication of the DANES working groups and general discussions. It is meant as the primary space for anyone in the community to ask questions, give updates, and generally have conversations on DANES and related fields and methodologies.

The mailing list is the more formal communication channel of the community. It is used to send out the monthly newsletter and give updates on meetings of the DANES working groups.

Newsletter

The mailing list sends out a monthly newsletter, at the beginning of each month, which includes updates on the world of DANES. The newsletter summarizes, while explicating jargon, important articles that were published in the past month, and highlights important previous publications related to DANES. It informs the DANES community of relevant conferences, both in the ANE field and the digital humanities and computer science fields. The purpose of the newsletter is to establish DANES in both the field of computer science and ANE studies, by developing joint language and terminology around important publications, and encourage network members to participate in conferences relating to both worlds.

Furthermore, after the publication of the newsletter there is a regular happy-hour meeting on the DANES discord channel for members to discuss and chat about what’s new in the community.

OpenDANES platform

The OpenDANES platform is an open access publication platform for pedagogical materials. It aims to create content that will be useful and informative to any who want to learn how to combine computational methods with ancient artifacts, regardless of their previous knowledge. It publishes tutorials, which provide step-by-step instructions on how to apply computational methodologies for beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels. White papers, such as this one, are published on the platform as well. Those can be anything from opinion pieces, updating the community on projects, introducing the community to general initiatives, or efforts of groups and individuals working on digital and computational studies of the ancient world. All contributions go through a peer-review process to ensure high-quality and usefulness to the community, as well as to acknowledge contributors’ academic work. Upon final publication, all contributions receive a DOI.

Additionally, OpenDANES includes the DANES resources, a dataset which collects free, online resources which can aid the DANES community members. It is a constantly growing dataset, and anyone is invited to contribute resources! See the instructions on the DANES Resources page.

Final Notes

Time will tell how the efforts of the DANES network will fare. The goals and activities will likely change and adapt as times goes by, and as technology changes and develops. The one thing that will not change is our overarching goal: being a resource and a hub for the community of those who study or want to study the ancient world computationally. Our focus will remain on sharing knowledge and expertise with the community, spreading the crafts and training new generations of artisans.

For that reason, we call out to all who want to take part in the community, whether as passive observers or active participants. Considering our past, present, and future, it is hard to imagine the field not changing drastically in the next decade. We want the ANE community to thrive in new research possibilities, without losing academic rigor to enigmatic methods and trendy AI jargon. In order to build a shared language and decide on our field’s future, we want as many as possible to join us: from the masters of the craft, to those on the fence on whether to become apprentices or not, to those who never thought they could have anything to do with this art. There is a place for everyone within the DANES community.

References

Anderson, Adam, Shai Gordin, Stav Klein, Bin Li, Yudong Liu & Marco C. Passarotti (eds.). 2023. Proceedings of the Ancient Language Processing Workshop (RANLP-ALP 2023). Shoumen, Bulgaria: INCOMA Ltd. https://aclanthology.org/volumes/2023.alp-1

Clark, Shmuel & Shai Gordin. 2023. ‘The Mesopotamian Ancient Place-Names Almanac (MAPA): A Gazetteer of the Uruk Urbanscape in the Age of Empires.’ Journal of Open Humanities Data 9(1), p. 20. https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.146

Gardin, Jean-Claude & Paul Garelli. 1961. ‘Étude des établissements assyriens en Cappadoce par ordinateur’. Annales 16 (5): 837–76.

Gordin, Shai, Shmuel Clark & Avital Romach. 2022. ‘MAPA: A Linked Open Data Gazetteer of the Southern Babylonian Landscape’. Interdisciplinary Digital Engagement in Arts & Humanities 3(2). https://doi.org/10.21428/f1f23564.8d442eea

Homburg, Timo, Tim Brandes, Eva-Maria Huber & Michael A. Hedderich. 2023. ‘From an Analog to a Digital Workflow: An Introductory Approach to Digital Editions in Assyriology’. Cuneiform Digital Library Bulletin 2023 (4). https://cdli.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/articles/cdlb/2023-4

Li, Bin & Shai Gordin (eds.). 2023. Proceedings of ALT2023: First Workshop on Ancient Language Translation (ALT). Macau, China: Asia-Pacific Association for Machine Translation. https://aclanthology.org/2023.alt-1.pdf

Plutniak, Sébastien. 2018. ‘Aux prémices des humanités numériques ? La première analyse automatisée d’un réseau économique ancien (Gardin & Garelli, 1961). Réalisation, conceptualisation, réception’. ARCS - Analyse de réseaux pour les sciences sociales / Network Analysis for Social Sciences Volume 2 (September). https://doi.org/10.46298/arcs.9236.

Sahala, Aleksi. 2021. ‘Contributions to Computational Assyriology’. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/332924.

Sahle, Patrick. 2016. ‘What Is a Scholarly Digital Edition?’ In Digital Scholarly Editing: Theories and Practices, edited by Matthew James Driscoll & Elena Pierazzo, 19–39. Digital Humanities Series. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers. https://books.openedition.org/obp/3397

Stötzner, Ernst, Timo Homburg & Hubert Mara. 2023. CNN based Cuneiform Sign Detection Learned from Annotated 3D Renderings and Mapped Photographs with Illumination Augmentation. IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCVW60793.2023.00183